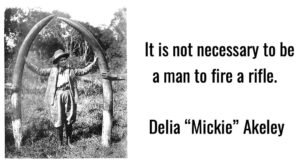

Old School Explorer, Mickie Akeley

Larger than life, Mickie Akeley was not afraid of many things, but she could not stand elevators.

Do you admire women who seize the chance to do what few people have done? To count down the days to National Kick Butt Day, October 14, I am honoring ten adventurous members of the Society of Woman Geographers. They were brave during an era when it took courage simply to don the trousers necessary to explore the Earth’s mountains, jungles, oceans, and skies. Today, I am honoring the outspoken Delia “Mickie” Akeley, who hunted for museum specimens alongside Teddy Roosevelt and didn’t hesitate to say she was too exhausted to enjoy chasing animals.

Mickie was an old-school explorer who married to taxidermist Carl Akeley. Today, we would call her a trailing spouse. But she did not trail for long.

During her first safari with Carl, Mickie quickly became a crack markswoman out of necessity. She recognized that a woman who could not take care of herself was a handicap on a safari. She frequently told her friends the story of why she learned to shoot.

“We were going quietly along the bush-covered banks of a stream looking for birds when a lion growled at us, and I became petrified with fright.”

Her young guide gently put his hand on her shoulder and whispered, “Very bad, memsahib! Very bad!”

“I am fully aware that it is ‘very bad,’” Mickie thought.

She collected her wits and backed up, clutching her shotgun, which she knew would not be lethal enough to save her from the lion. She recalled: “I don’t know what happened to the lion. His growl may have merely been a warning. He may have been as badly frightened as I was. But I did some heavy thinking as I walked back to camp.” She quickly learned how to shoot a 256 Mannlicher-Schoenhauser rifle. With only three birds to her credit as a marksman, she shot a charging bull elephant and dropped him six feet from where she stood. As Mickie wryly noted:

“It is not necessary to be a man to fire a rifle.”

Mickie admitted: “In a country where anything may happen and where even at night one must wake from a sound sleep and be ready for instant action, it would be folly to say there is no fear. But it is the sort of fear that stimulates, and perhaps it is that element that I have learned to love.”

“I do not feel especially brave. My work calls me to Africa, and I go gladly. It is hard to say what constitutes bravery. It may be a tautening of nerves in the face of danger; it may be the thrill of overcoming that stimulates and strengthens, in proportion to the thing to be overcome.”

She also admitted that she had come close to death a few times, once with a fever:

“I was delirious half of the time. When I wasn’t, I could hear the cook and my personal boy sitting outside the tent, discussing how they would prepare my body and arguing over how they would divide up my clothes. Each morning one of them would come in and ask politely if I was going to die that day. I always responded that I didn’t think so.”

But sometimes Mickie was too tired to feel the thrill of the hunt. President Theodore Roosevelt loved to tell the story about the time he went hunting with the Akeleys in Africa. They had been hunting elephants on Mount Kenya for several days. Mickie was tired. Not only was the climb steep, but they had to machete their way through the undergrowth on the side of the mountain, while the elephant would plow through the dense vegetation with ease. Mickie would take one step forward and slide two steps back. Frustrated, she pulled her hat down over her eyes so Roosevelt would not see the tears welling up.

Suddenly Carl saw an elephant’s footprint. He excitedly told Mickie, “My, dear, the elephants have been here.”

When Mickie did not reply, Carl drew closer to Mickie.

“I say! My dear, the elephants have been here.”

Mickie emitted a half-stifled sob.

“The damn fools!” Mickie said, causing Carl and Roosevelt to laugh.

Later, Mickie conducted some cutting-edge field studies in primate behavior and communication and became oddly attached to a small monkey they had captured. She planned to observe the primate in captivity and then compare its behavior in the wild to prove her hypothesis that monkeys are cleaner in the wild. Mickie liked the monkey so much that she decided to keep her. She named it J.T., Jr., after cartoonist John T. McCutchen, who was a member of the expedition party, even though the monkey was female.

When Mickie was not hunting big game or observing primates, J.T. was her constant companion. Carl became jealous of J.T. Once, when he left to hunt animals for the day, Carl left Mickie a note: “I love you. xxxx [kisses]. I want you with me darling. So much separation is hell for me. I’m jealous of your thoughts. Yes, I’m even jealous of the monkey. Oh, Mickie, can’t you tell how much I worship you?”

Despite Carl’s pleas for attention, Mickie became even more obsessed with J.T. At the end of the safari, she brought him home to live in their Central Park West penthouse. She bought J.T. a chair and spoon so that she could eat breakfast with Mickie and Carl. She kept J.T. for nine years.

Mickie and J.T.

As J.T. matured, she became destructive and possessive, tearing Mickie’s best dresses and anything that was unlocked. She pulled tablecloths out from under dishes, ripped pillows, and once took all of the beads off of Mickie’s new gown. J.T. would nip guests on the heels. When she bit Mickie deeply on the leg, Mickie hid the bite from Carl until she could no longer ignore the swollen and festering wound. Carl begged her to go to the hospital, but Mickie refused to leave J.T. Her husband arranged for a doctor to perform surgery in the penthouse. Mickie spent three months in bed, recovering. She understood that she had become obsessed with J.T., but she could not break the relationship. She wrote: “I had given up practically all my social life and many of my friends to devote myself to the care and study of this interesting creature.” When J.T. bit her again and almost severed an artery, Carl convinced Mickie to send J.T. to the National Zoo.

In 1918, Mickie left him to join the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I, and Carl filed for divorce claiming that Mickie had deserted him. She suspected (correctly) that there was “another woman” and countersued for cruelty. Her friends thought this allegation of cruelty was “the concoction of a spirited woman who felt wronged.”

Carl died two years after his divorce was finalized. He left his estate to his new wife, Mary Jobe. Mary quickly erased Mickie from Carl’s life in the books she wrote about him. A friend asked Mickie about Mary: “And what about No. 2, is she still seeking the limelight?” She was, and she effectively erased Mickie. The King of Belgium awarded Jobe the decoration of the Cross of the Knight of the Order of the Crown, Belgium’s highest honor for the work she did in the Belgium Congo during the two years she was married to Carl. In contrast, Mickie got little recognition for her nearly twenty years of safaris with Carl.

The Brooklyn Museum hired Mickie to travel to Africa to locate specimens. The New York World announced Mickie’s expedition under the banner Woman to Forget Marital Woe by Fighting African Jungle Beasts. Newspapers sensationalized this announcement, concentrating on Mickie’s appearance (she was then 49), comparing her to a modern-day Diana, goddess of the hunt:

With her silver hair modishly waved, delicate rosy complexion, soft voice, and quietly fashionable dark dress, she appeared anything but the common or motion picture conception of a lady lion-killer.

Instead, the journalist compared her to a “gracious private school mistress.” The reporter found it hard to believe that Mickie was going “once again into the deep heart of Africa, at a time of life when most women are ready to retreat to the side-lines” until he noticed her ivory tusk bracelet and her firm sapphire eyes.

Reporters erroneously reported that Mickie was traveling alone. Although she traveled solo to Africa, once she was there, she was accompanied by an entourage of local men. Newspapermen assumed that Mickie was incapable of protecting herself. The Calgary Herald made neither of these errors, noting that “For the first time, a woman—an American woman—will venture across Africa, unaccompanied by a white man.” The Calgary Herald reminded the public that it was Mickie who, upon hearing that an elephant had gored Carl, traveled 20 miles to find him, bring him back to camp, and nurse him back to health.

Mickey collected hyaenas, a lion, gazelles, antelopes, and a rare rodent during the expedition. She also collected memories of the cruelty of the Congo, which she tried to prevent along the way: the prostitution in the camps, the abuse of prisoners, and domestic abuse by the sultan. When the sultan sent a boiled human arm for her porters’ dinner, she did not intervene or judge as she knew cannibalism was a dietary custom. But she did lament:

“No wonder the sky sheds tears at night and the thunder booms and the lightning threatens. The Congo is cruel.”

Wildlife filmmaker Armand Georges Denis would have labeled Mickie as reckless. He met many women explorers during the filming of his feature-length films. Later, he would tell a reporter:

“I welcome the opportunity to tell women what is wrong with them, as explorers. And I hope that what I have to say may be discouraging enough to stop their wanderlust.”

Denis thought that women were much more reckless than men. “A man makes a cold calculation, and if the danger is too great, he will not take it. The average woman doesn’t think. She takes unnecessary chances or forces man to. Either he has to appear cowardly or follow after. It’s embarrassing.” For instance, Denis cites a woman who sees a lion cub. She says, “Oh, aren’t they cute” and walks up to them. “Trouble begins. And then the timid man has to rescue fearless woman again.” Another man claimed:

“One woman can cause more trouble on an exploring expedition than a whole horde of wild elephants, a tribe of wild and blood-thirsty savages, or a dozen lions and tigers ready for food.”

Mickie was one of a select group of members of the Society of Women Geographers who flew to Washington, D.C. in 1932 to attend a White House luncheon in honor of Amelia Earhart, who had just set the world record for the fastest trans-Atlantic flight. During the bumpy flight, Mickie wished she had taken a train. She was terribly afraid, but screwed up her courage, saying, “If Amelia Earhart can fly to Ireland, I guess I can be flown from New York to Washington.”

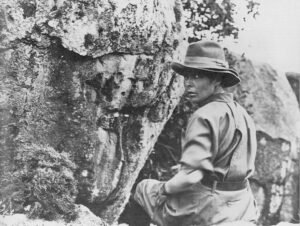

Members of Society Meeting Harriet Chalmers Adams in Washington, D.C.

for Amelia Earhart Luncheon at White House, 1932, Library of Congress

This fear remained with Mickie long after the plane ride. She told a reporter that she was afraid of elevators because she was in an airplane when it plummeted downward: “Ever since I have the same horrible sinking feeling when I go down in an elevator. I feel safer if I can get hold of something, but I clutched a woman’s dress one day and she thought I was trying to pick her pocket. So now I walk.” She once missed a meeting of the Society because she did not realize that she would have to take an elevator sixty-five floors to get to the Rainbow Room in Rockefeller Center.

In 1928, Mickie wrote a biography of J.T. and dedicated it to the memory of her husband: “To the memory of Carl Ethan Akeley whose life and work I shared for many years and who understood and loved ‘J.T., Jr.” as I did.” Carl, who was dead, could not challenge this statement.

-Comments-